Identifying the roles the narrator wants us to take on in the book Slaughterhouse-Five is a difficult undertaking. The book begins with an unnamed narrator who solicits trust from us as he explains the details of his “famous book about Dresden.” Then the narrator goes on to tell the story of Billy Pilgrim and how he became unstuck in time. Originally the narrator tells us that, “All this happened, more or less. The war parts anyway, are pretty much true” (1). What he says would lead someone to believe he is writing a memoir rather than about a fictional character. The book is about the character Billy Pilgrim but it is told from the point of view of our nameless narrator. The narrator asks us to look through his lens onto Billy’s story, but then to have that melt away to fully accept an narrative that centers around Billy rather than himself.

As I read through the book I was a very resistant reader. I was constantly reminding myself that the book was told not from Billy’s perspective but from the other narrator’s. I was reading and trying to make connections between what I knew about the narrator and what I knew about Billy. Why did the narrator chose to write about a fictional character rather than his own experiences? And why did he chose to do it in such a bizarre way? Billy’s story is not only about his war experiences but his life experiences and his encounters with aliens. The story is told through snippets of times in Billy’s life. One moment we are on the battlefield with him, the next we are at his wedding, and the next at a zoo in Tralfamadore! How can I become a capable reader and take ‘inferential walks’ to guess what will happen next in the text when I never know what time period I’ll be dropped into next? (Seitz, 146).

The book can be summed by a description of what a Tralfamadorian book is,

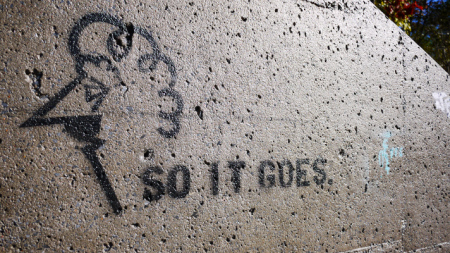

“There isn’t any particular relationship between all the messages, except that the author has chosen them carefully, so that, when seen all at once, they produce an image of life that is beautiful and surprising and deep. There is no beginning, no middle, no end, no suspense, no moral, no causes, no effects. What we love in our books are the depths of many marvelous moments seen all at one time” (112).

The narrator who wrote his “famous book about Dresden” has also written a Tralfamadorian book. He is either one of the aliens or he is the embodiment of their ideas. The book’s jumping around allows our minds to be in different places all at once just as Billy claims he can be. “Billy is spastic in time, has no control over where he is going next, and the trips aren’t necessarily fun” (28). Through the format of the book I can relate to Billy’s journey through time. In the middle of one of Billy’s memories I am pulled into another. The narrator wants us to accept Billy and all of his quirks. Although I can relate my reading experience to Billy’s delusions I can never accept the fact that the Tralfamadorians exist. However, I think that the narrator also wants us to see Billy as a warning. A warning of what happens when boys are sent into war.

In this text there could be almost two different “narrative audiences” as called by Peter Rabinowitz in “Truth in Fiction” (127). First we have the unnamed narrator who has chosen to write a book about the war through the perspective of someone else. His goal is to shed a negative light on war. We quickly lose our narrator and are pulled into Billy’s story. Although the narrator is still narrating during Billy’s story, another narrative audience could form to Billy’s perspective. Those in Billy’s narrative audience will nod in agreement with his retelling on alien abductions. There are people who will try to see how the narrator is fitting in and there are those who will just forget about him entirely.

Our narrator uses Billy as a mask to hide behind. Whether it be because his own story wasn’t exciting enough or because it was too much for him to remember, he chooses to write fiction instead of memoir for a reason. The narrator wants us to like and praise his book about Billy that’s why he boasts it is famous and elicits sympathy by saying, “This one is a failure, and had to be, since it was written by a pillar of salt” (28). Our role as readers is to adore the book and sympathize with the characters. It is an anti-war book, so we must understand the tragedies that war can bring. One of those tragedies is the broken mind of Billy Pilgrim.

What does it mean to write that “This one is a failure, and had to be, since it was written by a pillar of salt”?

LikeLike

The book refers to the story of Lot and his wife when it discusses what a pillar of salt is. After disobeying Lot’s advice and looking back at the destruction of the towns, Lot’s wife becomes a pillar of salt. Thus a pillar of salt can be described as someone can can’t help but look back at destruction or terrible events. The narrator is a pillar of salt because his whole book is about looking back at the horrible events of Dresden. The narrator says that, “People aren’t supposed to look back. I’m certainly not going to do it anymore” (28). So, in the narrator’s mind the book is a failure because he has not followed his own principles and has looked back in time. Thus making him a pillar of salt.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As was said, the relationship between the narrator and addressee is interesting in this text in reading for all four narrative audiences identified by Rabinowitz in “Truth to Fiction.” The most evident narrative audience and easiest role to adopt is that of the actual audience, or us, whoever is actually picking the book up and reading it. The addressee role as a part of the actual audience is simple to adopt. It involves picking up the book, then one begins to play the role because they write their own role without conforming to the expectations of the writer of who should be reading their work.

It begins to become more complex is when the reader adopts the addressee position of who the author ideally wrote the text for, or the authorial audience. As Rabinowitz describes it, “Since the structure of the audience is designed for the author’s hypothetical audience…we must, as we read, come to share, in some measure, the characteristics of this audience if we are to understand the text,” (126). While writing, the author makes assumptions about who will be reading and their level of knowledge. As a reader before entering into the role of addressee for the author we need to predict, or make assumptions about what the author is looking for in an audience.

For me, while reading Slaughterhouse Five, the narrator’s changing proximity to the story and to the main character made it difficult to distinguish between the authorial audience and the narrative audience. To consider these audiences and attempt to adopt the role of addressee for them both, one must do some real thinking to understand what both the author of Slaughterhouse Five is asking the reader to become, and the difference between the authorial audience and the narrative audience. According to Rabinowitz, the narrative audience is the audience that the narrator of the story, which can be the fictional author of the piece, is writing for. This audience possesses some knowledge that the actual audience does not because they exist within the imagined world of the narrator. To understand the narrator and who they are writing for, the reader has to understand the purpose. However, if author’s intended audience is different from the narrator’s audience, it is hard for me to flip between becoming an addressee for both and distinguishing between which I am being at specific moments in reading. To me, it sometimes feels that if the narrator is written by the author, then the author’s intended audience would be the same as the narrator’s actual audience because it is all created at the author’s discretion.

Rabinowitz describes the final audience, or the ideal narrative audience as, “The audience for which the narrator wishes he were writing and relates to the narrative audience in a way roughly analogous to the way that the authorial audience relates to the actual audience,” (134). By that, Rabinowitz means that the ideal narrative audience is the narrator’s intended audience. So to fully understand the fictional author, or narrator, and what they are hoping to convey through the story a reader has to understand who the narrator wants their audience to be. This takes a deep understanding of the narrator and their purpose which, in Slaughterhouse Five, at times feels unidentifiable.

LikeLike

When reading Slaughterhouse Five I had some problems submit to this book compared to other books. The relationship between the narrator and the address was difficult for me to really submit to because the writing style was very off kilter. Initially I found this to be pretty humorous, but as I got further into the book I became more and more resistant.

Slaughterhouse Five was a book that I have been wanting to read for a long time but after reading it for this class the book didn’t really grab me in any sort of way.

When discussing the reading experience of Slaughterhouse Five I would say it was a better experience that the reading experience I had with Girl on the Train. The reason for that is because I was an extremely resistant reader to that book because that book was a mystery book and that was something that I wasn’t as familiar with. However,when reading something like A Wizard of Earthsea I was a lot more submissive because it’s a fantasy book and that’s a genre that I really like; but it was extremely hard for me to submit to this book, and I wasn’t sure why. I love dark humor and science fiction, but this book didn’t really do anything for me, and it was very hard for me to submit to it.

LikeLike

The potential role between the narrator and the addressee is definitely difficult to uncover in Slaughterhouse-Five. I think it’s interesting that the narrator deems himself unreliable with the very first sentence in the novel by saying “all this happened, more or less. The war parts, anyway, are pretty much true” (1). In my opinion, this is an odd way to begin the novel. It’s almost as if the narrator wants us to question whether or not his story is entirely true or not. In relation to the narrator and addressee roles in this novel, maybe the narrator wants his addressee to be skeptical about the events that take place in the story. If that’s the case, then I’m a perfect fit as an addressee. I am, indeed, very skeptical about the alien abduction parts in this novel.

On another subject: I like how Larissa brought up the proposal that maybe this novel was written the way Tralfamadorians would write a book, with “no beginning, no middle, no end, no suspense, no moral, no causes, no effects” (88). In a way, this is similar to how our narrator in Slaughterhouse-Five presents the story of Billy Pilgrim. In regards to the story of Billy Pilgrim, there is no beginning in terms of telling his story in a linear way; there is no ending in terms of how Billy Pilgrim dies since this is revealed towards the middle of the novel; and there is no particular middle in terms of a rising climax in Billy Pilgrim’s story either. The events of his life are all mixed up and in no relevant particular order. This could definitely be seen as a book from Tralfamadore. The story is narrated in a way that allows the reader to see Billy’s life all at once, only this is not possible in “our world” since time doesn’t work like that—time is told in a linear fashion in our world. But it is almost as if the narrator attempts to make us see Billy’s life as if it were a Tralfamadorian looking in on his life—as “many marvelous moments seen all at one time” (88). This is a very interesting concept that I never thought about before. I am glad that Larissa brought this up.

I think the pillar of salt idea was a good thing to mention as well. Maybe our narrator tells the story through Billy’s eyes because the narrator is skeptical about looking back and telling details about his own past (afraid that he’ll turn into a pillar of salt)—so he told the story of Billy instead. This would explain why our narrator originally expresses his interest in writing a novel about his experience in the war, but instead ends up producing a story from Billy’s perspective.

The narrator also has a strange way of reminding us that he still exists while he’s telling Billy’s story. Throughout random parts of the story, the narrator will jump in and mention that he was there to witness something. For example, the first time this happens is on page 67, and I honestly forgot all about the narrator at this point because I engrossed in Billy Pilgrim’s story. As our narrator tells us about Billy’s encounter with Wild Bob, all of the sudden he says, “I was there. So was my old war buddy, Bernard V. O’Hare” (67). This was incredibly random, and it surprised me. I think the narrator could have included this because he didn’t want his addressee to forget that he was telling the story. Maybe he felt a bit left out since the story was supposed to be about his experience, but instead ended up being about Billy.

LikeLike